Talking treaty: A Ngāi Tahu perspective

Sue Wards

21 February 2024, 4:04 PM

Matua Darren Rewi PHOTO: Wānaka App

Matua Darren Rewi PHOTO: Wānaka App“This was the command thy love laid upon these Governors. That the law be made one, that the commandments be made one, that the nation be made one, that the white skin be made just as equal with the dark skin.”

This plea by Ngāi Tahu rangatira Matiaha Tiramōrehu to Queen Victoria in 1857 (asking the Crown to provide adequate reserves of land for the people as agreed under the terms of the land purchases) remains the Ngāi Tahu “policy” on the Treaty of Waitangi, Central Otago kaumatua Darren Rewi told a group of locals in Wānaka last week.

“It is better to be at the table and move forward for the country than it is to be fighting backwards and forwards,” he said.

“Ngāi Tahu will always try to be at the table.”

The Treaty of Waitangi was signed by eight out of around 48 Ngāi Tahu chiefs in 1842. Nothing was straightforward about the signing, including the fact that June, when the signing took place, was mutton bird season and many of the iwi were busy at the mutton bird islands south of Bluff.

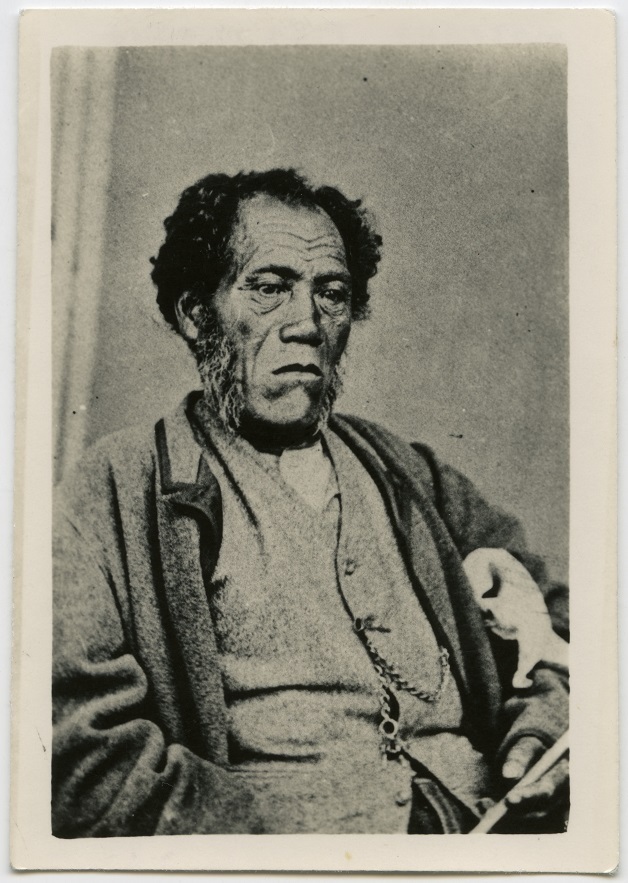

Ngāi Tahu rangatira Matiaha Tiramōrehu PHOTO: Ngāi Tahu

Another complication was that of a number of smaller tribes in the South, Ngati Mamoe chiefs did not sign the document. In addition, chiefs would draw their moko for their signature, but were sometimes rushed if the agents considered it was taking too long, and made to write an ‘X’ instead.

“We’re struggling to identify who signed the treaty,” Darren said.

That document, incidentally, was made of lambskin, like the original treaty signed in Waitangi but unlike the seven other parchment treaty papers. After the signing, the Ngāi Tahu ‘papers’ were thrown into a box and eventually partially eaten by rats.

The rat-chewed document seems symbolic of how the treaty worked out for Ngāi Tahu. Despite the tribe signing land sale contracts with the Crown for around 34.5 million acres (approximately 80 percent of the South Island) the Crown didn’t even allocate one-tenth of the land to the iwi.

Neither did it pay the fair price it had agreed to.

The Neck, at the head of Lake Hāwea. PHOTO: Wānaka App

Ngāi Tahu continued to seek redress from the Crown until the Ngāi Tahu Settlement Act was signed in 1998.

“Ngāi Tahu has a vision for what we say Te Tiriti is,” Darren Rewi told the gathering of around 30 people at Wānaka Library on Thursday (February 15).

“In order to understand the context of the Treaty for Ngāi Tahu we need to understand who’s who and who’s where.”

Darren told stories which “bring us back into this area”; including the early Māori arrivals to Hāwea, and the vital role of the Neck (the isthmus separating lakes Hāwea and Wānaka), which was a kāinga mahinga kai (food-gathering settlement) and kāinga nohoanga (settlement).

The “huge harvesting site” was lost (drowned) when Lake Hāwea was raised to store water for hydroelectric power generation in 1958. As compensation, Ngāi Tahu were given the Wānaka area now known as Sticky Forest through the South Island Landless Natives Act.

The forest is held by the Crown for around 1,800 descendants of 57 original Maori grantees, some of whom are seeking to have it rezoned for residential development. Queenstown Lakes District Council has rejected the submission and the case was heard by the Environment Court in December last year. A decision has not yet been announced.

Go deeper: Sticky Forest ‘conundrum’ to go to Environment Court in July

The unresolved situation of the land and the challenge of identifying its many heirs now sits in the area “like a bad smell”, Darren said.

He said the issue also raises the question: “If you’re going to build a marae here, [which ancestor] is it going to be under?”

Each of the 18 Ngāi Tahu hapu is based around an ancestor, and each hapu is represented by a runanga which has a relationship with territorial authorities such as district councils (unlike in the North Island where these relationships are with iwi). Ngāi Tahu ancestors moved around the South and their descendents have claims all over the region.

“Politically everyone just leaves it alone,” Darren said.

Treaty principles

After the kōrero Darren told the Wānaka App the Treaty Principles Bill proposed by ACT Party leader David Seymour raises the issue of “coming together and moving together as one”.

“Now we are having to defend what [Treaty] principles mean,” he said.

“There are always two stories, there’s always a lot to unpack.”

But Darren is certain “the younger ones will see us right”.

He referenced Sir Ranginui Walker’s well known quote that race relation problems in New Zealand “will be resolved in the bedrooms of the nation”.

Darren will present a second part of his Treaty kōrero at the library in the coming weeks.